|

Amerindian

Villages

|

Like Stonehenge in England, the dating and

complexity of the villages of the People of the Longhouse

are under continuing analysis. Some sites, such as the Nodwell

site on the eastern shore of Lake Huron, have proven to

be sites where tribes have lived for many hundreds of years.

(See Dr. Rankin's research

on this area.)

Most scholars, archeologists and historians

agree that both the Iroquois and the Algonkian tribes, the

Eastern Woodland Indians, lived in villages built around

longhouses. The number of longhouses and the nature of the

longhouses within the structures varied according to location

and date. Early longhouses faced a variety of directions.

Ultimately they were all oriented along a northwest-southeast

line so that the smallest surface area faced the prevailing

winter winds.

|

|

Woodland villages consisted of a series of longhouses which

were occupied by from five or six to as many as 25 families.

The Nodwell site is said to have housed up to 500 people

for 20 years at a time. The Wendat village in Midland Ontario

had far fewer.

The longhouses were surrounded by a double palisade of

vertical wooden poles. Within the enclosure were also summer

wigwams, shelters for dogs and bears who were kept as pets

and then, sometimes, sacrificed and consumed during religious

festivals. Racks for drying skins or bark and storing canoes

were also within the palisade.

All the materials used to make the longhouses was perishable

and most extremely flammable. The reconstructed villages

found in Brantford and Midland are reconstructed from drawings

and legends. The footprints of longhouses can be accessed

by trained archeologists, but information on precisely how

many villages there were in Ontario at any given time is

sparse.

|

|

|

Fortification

Woodland Cultural Centre Brantford

The Woodland Cultural Center

in Brantford has examples of most of the building types found

in villages in that area. It is an accurate representation of

pre-contact building styles.

Here is an example of a longhouse

(detailed below). Notice that the palisade in this case has

only one row of poles. These poles are made without the use

of metal tools.

Behind the longhouse is a lean-to

either for protecting wood from the elements or for storing

grains etc.

|

|

|

Wendat Village

Fence Posts

The Wendat Village in Midland is another authentic

recreated village representing pre-contact First Nations peoples.

Prior to the influx of metal tools, the posts

used both for the palisade fortifications and for tools would

have been quite small. Here we see the layout of the village

with fence posts having a diameter of 10 to 15 centimeters (4

or five inches).

|

|

|

Saint Marie among the Hurons

Palisade

Saint Marie among the Hurons is also a reconstruction

of a First Nations site, but there are two distinct differences.

First Saint Marie is a reconstruction of a post-contact

village made by the French for the visiting Wendat. It was never

made BY the Wendat themselves, so differences in construction

would have been inevitable. Secondly, the use of metal tools

would have made a huge difference even then.

Jared Diamond in his book Guns, Germs and Steel

outlines the differences in the evolution of peoples on different

continents relative to the introduction of metals for use both

in construction and in defense, and in the introduction of germs.

|

|

|

Celtic Village - Wales

Palisade

Like the villages found on this site, St. Fagan's

Celtic Village in Wales is a reconstruction made after study

of the excavated remains of a village from the early Iron Age.

The site is defended by a palisade made in the same way as the

palisades in Ontario. It was also defended by a ditch, like

the Avebury Circle.

Again, Jared Diamond offers a good discussion

on the evolution of building styles relative to available tools

in his book Guns, Germs and Steel

|

|

|

Saint Marie among the Hurons

Palisade

The fences in Saint Marie are obviously made using

metal tools, and in some cases gas powered tools. Note that

the posts are decidedly thicker than those found in the pre-contact

villages. The height is almost the same, but the tops of these

posts had to be tapered to make them shorter where the termination

of the pre-contact posts is natural.

First nations peoples used fire to cut the wood.

This method would take a lot longer.

|

|

|

Fort William

Palisade

The palisade in Fort William is also a reconstruction

of a post-contact fence. Fort William was first established

around 1679, just a few decades after Saint Marie among the

Hurons. It was used as a trading post where the French could

trade furs with local First Nations tribes.

The reconstruction of Old Fort William is intended

to portray the fort as it would have been in 1815. As can be

seen, the fence in this case is made of straight timbers much

larger than those found above.

|

|

|

Fort William - Fence

An exterior fence also shows the use of metal

tools. It would have been difficult for the First Nations peoples

to fell trees of this size and impossible for them to split

them without the use of metal tools.

By the time this fence would have been built in

1815, most of the native population of Canada had succumbed,

not to the superior power of the British or French army, but

to the micro-organisms introduced to them, either by mistake

or by intent, which killed them by the thousands.

|

|

|

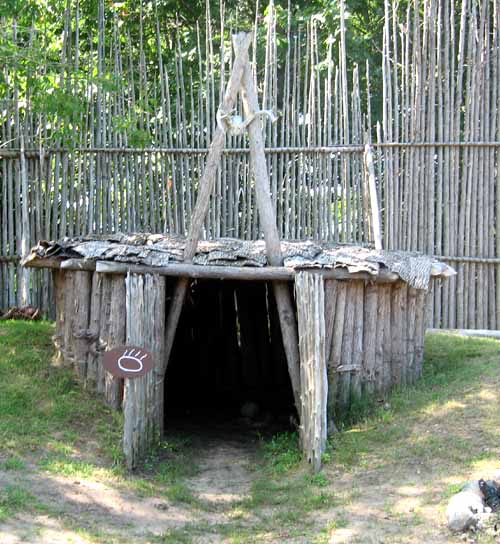

Sweat Lodge - Kanata

A sweat lodge is used during religious ceremonies

as a sacred place for communal prayer. As part of a wedding

ceremony or a funeral, or during the naming of children, the

extended family will gather in the sweat lodge to sing and pray

to the spirit world.

Large stones are heated on the fire and then rolled

into the lodge. At appropriate times, generally after a prayer

or dedication, a small amount of water is poured onto the stones

and steam fills the room. The steam cleanses the body and purifies

the soul.

|

|

|

Wendat Village Midland

This sweat lodge as well as the one above is situated

inside the village, in this case the Wendat village in Midland.

These villages are extremely useful in giving an idea of the

variety of buildings constructed by the First Nations peoples,

but the locations of buildings is determined by the physical

limitations of the site.

Sweat lodges would more often be situated away

from the village in a spot more conducive to meditation and

concentration on spiritual matters. Similar to the traditions

of Chinese Feng Shui and Celtic/Wiccan methods of spirit attraction,

the positioning of the sweat lodge is crucial to its success.

The sweat lodge was the place to attain spiritual

cleanliness. The site would be prepared and supplied with an

adequate amount of both stones and firewood so that the ceremony

could continue as long as necessary.

|

|

|

Central

Pole - Wendat Village Midland

Close to the main entrance to the village would

be a central pole decorated with feathers, bones or animal horns

to pay homage to the spirit of the animals and birds that surrounded

the village as well as to the courage of the hunter. European

coats of arms, tapestries and heraldry used similar imagery

and, particularly in medieval times, for similar reasons. The

central pole was the gathering place for announcements, festivities

and ceremonies. It was the 'flagpole' of the village.

|

|

|

Saint Marie among the Hurons

The Jesuits were interested in converting the

'savages' to Christianity. Beside their own compound and within

the fortification they built a small village where the Wendat

could come to visit and pray. Within that compound was a hospital

for both Wendat and French. Only the long house and a few wigwams

were constructed since the Wendat had their own villages and

simply visited here. Sweat lodges would have been forbidden.

|

|

|

Shelter

Wendat Village Lean to

Prior to the metal ax, the Wendat used fire to

cut through wood. This shelter has the cutting pit and the stack

of wood cut into pieces by the fire. This type of shelter would

also have been used to produce pottery.

Pottery was made from clay mixed with rock quartz

as a binding material. Vessels were made for purposes of cooking

as well as for storage. Charms and amulets were also often made

of clay. All clay pieces were decorated with sharp bone, coloured

clay or chunks of coloured quartz.

|

|

|

Lean

To Kanata

Lean-tos of this kind were scattered throughout

the village.

Each family would keep their valuables within

the longhouse with them. Often a large hole was dug and the

precious objects would be buried beneath the section of the

floor that the family occupied. There were no large chests or

significantly large ceramic vessels for storage.

|

|

|

Lean to

Saint Marie

Both Saint Marie and Fort William have lean-tos

in various places. These would have been made with larger wood,

again, because of the introduction of metal tools.

The building methods for these shelters would

have been similar to those used by the natives, but not dissimilar

to structures found in Europe used for the same purpose.

|

|

|

Boat House

Wendat Village

Most First nations villages were situated close

to a waterway both for protection and for fishing. Two types

of canoes were made. One was a long boat, up to 8 meters ( 24

feet) long used to transport corn, pelts or people over long

distances. The other were shorter vessels for independent travel,

fishing and sport. The canoes were kept from the elements in

lean tos like this.

|

|

|

Production

Drying

Racks

Wendat Village

Both animal skins and building bark were dried

on drying racks throughout the village.

|

|

|

Wendat Village

Building Supplies

The Wendat depended on fire for both heating and

cooking. Most of their buildings were constructed of dried wood.

Clearly a supply of building material would be needed in case

of fire either to the longhouses or to the surrounding palisade.

The poles would be made ready for use then stored

in an upright position to prevent rot and to maximize space

within the village.

|

|

|

Longhouses

|

As Ontario is quickly being cemented over, archeologists

are scrambling to do valuable research on pre-contact villages

before they are removed to provide room for yet another

beige on beige Bichon Brunch suburb.

Oval communal housing remains dating from the

first millenium AD have been identified on Princess Point

near Hamilton and on Kipp Island New York. For more information

see the Ontario Archeological Society site.

Early European travelers made sketches of and

described the villages and longhouses used by First nations

peoples. In Ontario, all First Nations peoples are people

of the Longhouse. The people of the Six Nations who moved

up to Ontario in the 18th century also lived in Longhouses.

|

|

Father Joseph-Francoise Lafitau, a Jesuit missionary, describes

the buildings thus:

"These pieces of bark lap over one another like slate.

They are secured outside with fresh poles similar to those

which form the frame roof underneath, and are still further

strengthened by long pieces of sapling split in two, and

are fastened to the extremities of the roof, on the sides,

or on the wings, by pieces of wood cut with hooked ends,

which are regularly spaced for this purpose." (Nabokov

and Easton, p. 82)

All of the longhouses below are reconstructed in the 20th

century from excavations and descriptions like the one above.

|

|

|

Longhouse

- Kanata

The Longhouse was a permanent

winter residence for the First Nations peoples, and thus well

constructed for continual use.

The buildings are built along

a long wooden barrel vault, built very high to accommodate the

fire that burned perpetually within, in the winter for warmth

and in the summer to discourage the black flies and deer flies

that were a constant bother.

Each village had a different

finish style, but the shape remains constant.

|

|

|

Inside

the warmest place in the winter, was beside the

fire, so people slept on the floor near their family fire. The

shelves served as storage during the winter months. In the summer

the people slept on the shelves or built family wigwams outside.

In the larger longhouses the children sometimes

slept on the upper levels because they were warmer. Storage

was for the very top levels. The lower levels were for adults

to sleep in.

|

|

|

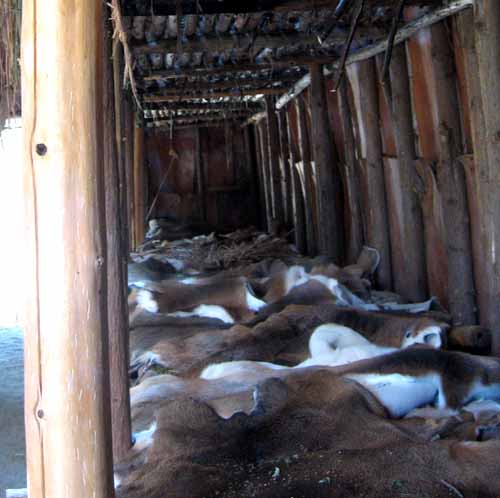

|

Kanata Village

The Kanata Village reconstruction gives an excellent

example of the methods used to construct the various platforms.

Ladders would have been used to access the upper

levels.

|

|

|

Kanata Longhouse

The exterior shows the securing of the frame and

the bark as described by Father Lafitau. Very large pieces of

bark were used. These would have been extracted from the trees

in the spring and left to dry on the drying racks, shown below,

over the summer.

|

|

|

Kanata Longhouse Interior

The inside frame of the longhouse was constructed

by a series of saplings secured into the soil like the palisade

was, then bent to created a vaulted roof. In the roof there

were skylights above each firepit allowing the smoke to escape.

These skylights also provided light for the interior of the

longhouse. There were no other windows.

The walls were reinforced with saplings on regular

intervals. The frame, bark, and reinforcing would have been

secured with leather thongs and strong twine made from reeds.

|

|

|

Wendat

Village Midland

The longhouse at the Wendat Village in Midland

is a reconstruction of a pre-contact structure. The exterior

has not yet been reinforced, but this shows how the bark was

attached to the wooden frame.

The edges would have been stitched onto the interior

frame, again, using strips of leather or strong reed twine.

|

|

|

Wendat

Village Midland

The doorway has an exterior porch that acts as

a buffer to the strong summer sun.

|

|

|

Wendat Village Interior

The longhouse at kanata Village in Brantford is

an excellent example of building methods. This village in Midland

is also equipped with the various materials the people would

have had inside the longhouse. Snowshoes would have been necessary

in winter. Netting was used for fishing. Reeds and grasses were

hung from the roof to be used in a wide variety of applications.

|

|

|

Wendat Village Extended Bed

The lower level platform was covered with skins

from the hunt. These would have been used as bed coverings for

warmth and comfort.

|

|

|

Wendat Village Fire

Along the floor were a series of fire pits. Two

families would have shared the fiercest, one on either side

of the longhouse.

Corn was a cultivated crop for most people of

the Longhouse.

|

|

|

Wendat Village Midland

Again, here is the skylight used for ventilation

as well as light.

|

|

|

Saint

Marie among the Hurons

The Longhouse at Saint Marie among the Hurons

has a porch on each end. These would have been useful for keeping

out the hot summer sun and for protecting the doors from harsh

winter winds.

This longhouse was made by the Jesuits to encourage

the native peoples to visit. Inside there is evidence of post-contact

materials such as blankets and metal knives.

Notice that there is smoke escaping from the doors

and skylights.

|

|

|

Saint

Marie

The site is staffed by a group of knowledgeable

people who keep the fires going inside the Longhouse like they

would have been during actual use.

Open central fire pits were used by Europeans

for many millennia. The term 'atrium', now used for the central

open hall or garden of a building, was originally the central

area where the fire was kept.

|

|

|

Saint

Marie among the Hurons

The roof on this longhouse is well secured and

the final exterior supports are also in place.

|

|

|

Saint

Marie

This detail shows how the roof would have been

secured and how the poles reinforce the design.

|

|

|

Saint

Marie

Two longhouses are found at Saint Marie. Some

sites, such as the Nodwell site, had up to 12 longhouses within

the palisade. Up to 500 people could live in the community cultivating

the local land.

|

|

|

Wigwams

|

The wigwam was the less permanent summer structure.

Round wigwams were built for hunters and people wanting

to have a portable home for travel. Larger wigwams were

built for families who wanted to live in a more private

setting for the summer months. These could have been established

wither within the palisade or on a more picturesque spot,

like a summer cottage.

|

|

The difference between a wigwam and a teepee is the finish

material. Wigwams are made with a variety of tree bark.

They used ash, birch, chicory, elm and hickory. Teepees

are covered with animal skins.

This site will tell you how to build a wigwam.

http://www.nativetech.org/wigwam/construction.html

|

|

|

Wendat

Wigwam

The first wigwam within the walls

of the Wendat Village in Midland is a circular structure covered

in large sheets of hickory bark.

This would have been the village

guest house, used to house visitors from another village.

|

|

|

Wendat Wigwam

Another, slightly larger, structure

with a porch is made out of the same material. This was the

Shaman's lodge. The Shaman or medicine man held the same esteem

within a community as the priest or doctor would have held in

the European community. In this case the Shaman was both priest

and doctor.

The Shaman is the person in the

village most in touch with the spirit world. His wigwam would

house the various okis or charms that assist him in his work.

|

|

|

Saint

Marie Wigwam

Saint Marie among the Hurons

has several wigwams. This one is a circular structure made with

hickory bark.

|

|

|

Saint Marie Wigwam

The back of the wigwam shows

that the construction was very similar to that of the longhouse;

the bark was attached like overlapping shingles.

|

|

|

Saint Marie Wigwam

Another circular wigwam on the

site shows a similar method of construction. The door on this

wigwam is much bigger than on the other.

|

|

|

Fort

William

The reconstruction of Fort William

near Thunder Bay has a wigwam built with birch bark. This wigwam

is outside the Fort's palisade. The Fort was established primarily

as a trading fort, and then as a military fort. The First Nations

peoples would bring their furs here to trade.

|

|

|

Saint Marie

A larger type of wigwam has been

reconstructed on the Saint Marie site.

This would have been a wigwam

used as a summer residence by a family. The exterior finish

is birch bark.

The guide, Autumn, is of Wendat

origin and is extremely well informed and helpful. The people

who have First Nations blood dress in traditional costumes.

|

|

|

Saint Marie

The interior is light and bright.

Here we can see the framing of

the walls using saplings that meet at the center in the roof.

|

|

|

Saint Marie

This detail shows how the exterior

finish would have been stitched onto the frame with leather

strips.

|

|

|

Saint Marie

This is the type of undulating

exterior that Frank Gehry makes on some of his structures. The

colour of the bark and the texture are absolutely gorgeous.

|

|

|

Teepees

and Igloos

|

This section is still under construction. If

anyone knows of a good igloo in Ontario, I would LOVE to

shoot it.

Teepees are used by the

First nations peoples on the plains of Canada, what is now

known as Manitoba and Saskatchewan. They were used by the

people who followed the buffalo herds because they were

fairly easily transportable and there was no shortage of

buffalo hides. Teepees in the far west of Ontario, Thunder

Bay and other regions, are occasionally constructed using

birch bark. The majority are covered with animal skins.

|

|

The number of poles used in the center of the structure

was an indicator of how many people inhabited the structure

and how important they were.

|

|

|

Teepee

This is a reconstruction of two

teepees near the First Nations reserve in Southern Ontario.

|

|

|

Teepee

The structures are very handsome

and well made.

|

|

|

Teepee

This detail shows how the doors

were attached.

|

|

|

Teepee

The 'oculus' or hole in the roof

where the poles meet would have been useful both for light and

for heat to escape.

|

|

|

Teepee

|

|

|

Igloo

I have yet to find a real igloo.

But I will

|

|

|

Modern

Architecture by First Nations Architects

|

The modern architecture section is still in

the development stage. The good news

is you won't be tested on it!

|

|

|

|

|

Museum

of Civilization

Douglas Cardinal

Like many architects who have work in Ontario,

Cardinal has done beautiful buildings of a similar nature throughout

the world. The most apt phrase to describe his buildings is

'ribbons of stone'. The forms intertwine, undulate, and are

organic in the real sense of the word.

|

Ottawa Ontario

|

|

Museum of Civilization

Ottawa - Cardinal

The Museum of Civilization in Hull - Ottawa -

its across the river - is one of the best examples of his style.

|

Ottawa Ontario

|

|

First

Nations Religious Structures

|

First Nations peoples have the same

type of profound relationship with nature that was found

in the Celtic culture. The traditional places of worship

are either part of the naturally occurring landscape, some

say created by the Great Spirit, others are manufactured

parks and sculptural mounds. The importance of certain areas

in Canada that have historically been places of First Nations

worship was brought to light in 2004 by Cathedral Grove

BC.

http://www.cathedralgrove.se/

The Six Nations, Wendat and Algonkians

were not the first tribes to settle in Ontario. Tribes from

the south had settled here many millennia before the pre-contact

tribes found here in the 17th century. The first structure

in Ontario dedicated to worship is not a building, but an

earth sculpture, made by the an earlier tribe whose belief

system included the Great Serpent.

The Ho-de-no-sau-nee, the People of

the Longhouse, believe that the Giver of Power controlled

the universe and the Great Serpent

was subsequently demoted.

Like their European counterparts, the

various tribes in North America were engaged in blood feuds

on a massive scale during the 12th, 13th and 14th centuries.

The League of the Great Tree of Peace, brought about by

Deganawidah, in about 1450, was the start of the Six Nations

and effectively the beginning of the end of intertribal

conflict.

While the Neutral, Tobacco and Huron

people did not join in this union, they were affected by

it in their own thinking. Festivals and feast days became

more focused on universal peace than they had earlier. The

communal quality of the Longhouse peoples was extended to

neighbouring tribes.

One spiritual ritual that was unique

to Ontario is Yandatsa - the Feast of the Dead. This

was a Wendat festival, written about by Jean de Brébeuf

in 1636. The feast took place once every ten or twelve years.

At this feast the corpses of dead relatives were exhumed,

transported to ,and reinterred at a common grave. All the

various tribes in the area would meet at the common grave

and bury their respective relatives together thereby promoting

social solidarity.

Religious festivals took place in the

longhouse of the Faith Keeper. Some of these festivals,

like Thanksgiving, were adapted by the early settlers and

integrated into North American society. Like the religious

activities of the European tradition, the People of the

Longhouse had regular morning prayers, rituals to acknowledge

and name children, and ceremonies to recognize marriages

and deaths. Most tribes were monotheistic with the belief

in a central Great Spirit who was attended to by a series

of lesser spirits.

|

|

North America was discovered by the Europeans

when they were looking for a passage to the East and all

the riches that lay there. The first visitors, shortly after

Champlain's visit (1603 - 1608) were adventure-seeking traders

interested in exploring the possibilities of this unexpected

new land, and aiming to exploit its commercial possibilities

to the fullest. As often happens, those interested in commercial

gain were followed closely by those interested in religious

gain.

A special sect of Jesuits, calling themselves

the Society of Jesus, marched in to claim the Amerindians

for their God. "Brave, devout and intolerant, as only

the truly idealistic can be" (MacRae, p. 5), the Jesuits

set up many missions throughout northern Ontario, Saint

Marie among the Hurons (1639 - 1649) being the largest

and most prosperous. At its height, the mission had sixty

Frenchmen and over 200 Wendat who visited from time to time.

Following a long tradition of self-sufficiency in monasteries

and religious missions (see www.Ontarioarchitecture .com/ClassRomanesque.com),

the mission was self-sufficient for a good ten years.

While the Jesuits were sincere in their

efforts to bring salvation and spiritual happiness, as they

knew it, to the First Nations peoples, their mission was

doomed to failure. The large trading centers had moved west

to Fort William, now Thunder Bay, and east to Quebec, so

there was dwindling financial aid from France. More importantly,

the Jesuits had been preceded by 30 years of traders who

brought metal goods, blankets and beads as well as tuberculosis,

influenza, measles and smallpox. The First Nations peoples

had no immunity to the new European diseases and consequently

died by the thousands simply through contact with the white

people. Several tribes of First Nations peoples decided

that the Jesuits should take their diseases and leave them

to heal themselves. They started to attack the settlement

and eventually forced the Jesuits out of their mission and

over to what is now known as Christian Island. The Jesuits

burnt the mission to the ground before they left. The current

site has been rebuilt according to modern ideas of rustic

simplicity.

Once the mission had been disbursed,

the majority of Weeniest melted back into the forest to

resume their religious connection with the Giver of Power.

The next 150 years saw the immigration

of a wide variety of European peoples in search of political

and religious freedom. Like many new Canadians today, they

brought their intolerance, squabbles and prejudices with

them. In the early years when the going was really tough,

they lived relatively peacefully as neighbours. Settlers

moved into areas where they identified with a certain clergyman

or church, but even when not in agreement with the local

denomination, the harsh realities of life during the rebellions,

the revolutions and finally the Treaty of Paris, they lived

in relative harmony.

After the Treaty, most First Nations

tribes were relocated. The Six nations were allies of the

British during the war and consequently they received large

tracts of land, one portion of which is located along the

Grand River. Many Iroquois left northern New York and relocated

in Ontario. The Mohawks were moved into the area now known

as Brantford. By this time the majority of First Nations

peoples had been converted to Christianity. The oldest Christian

church in Ontario still standing is the Royal Chapel of

the Mohawks in Brantford.

|

|

|

Serpent

Mound

The Serpent Mound has rested

on the side of Rice Lake, just north of Lake Ontario for almost

eighteen centuries. It was created there by early Amerindians

who migrated up from the south bringing corn, squash and tobacco

with them.

This is the most northerly of

a series of serpent mounds created in North America. The next

closest to this is the Serpent Mound in Ohio.

|

|

|

Serpent Mound

The Great Serpent was the major deity for the

southern tribes of Amerindians in the first millennium BC. The

people of the longhouse, however, decided that the Great Spirit

was the one true god of their part of the world, and the serpent

was demoted.

The mound continues to provide a resting place

for the serpent people.

|

|

|

|

Serpent Mound

The Mississaugas of Rice Lake recognize the significance

of the mounds and the importance of maintaining the sacred burial

grounds. They are proud to be stewards of the land which is

now a provincial park in the summer with cabins, kayaking and

canoeing, and beautiful hiking trails.

As far as physical structures of religious buildings

are concerned, there are very few. Most of the other buildings

are Christian and thus a result of European intervention.

|

|

|

|

Saint

Marie among the Hurons

Saint Marie was the earliest Christian church

to be built in Ontario in 1639. When the Jesuits left the mission

in 1649, the church was burnt to the ground. This is a 1970s

reconstruction based on what was then thought to be rustic.

Marion MacRae speculates that the original church must have

had much more pleasing proportions and much more adornment since

the builders had come from Rouen, France.

|

|

|

Jesuit Chapel at Saint Marie

Along with the church shown above, the Jesuits

at Saint Marie among the Hurons

needed a private chapel for personal devotions. Once again the

proportions and the detailing are much more 1970 than 1640.

The first Jesuit building was Il Gesu in Rome,

shown below, the first truly Baroque church of Post-Reformation

Europe.

|

|

|

IL Gesù,

Rome

1568 -1584

This first Jesuit church provides the model for virtually every

Jesuit church in colonial America, Africa and South America.

The scrolls, the double pediments, one Florentine one triangular,

the multi-layered pilasters, are characteristic of the Baroque

style.

With this in mind, and having no photographs or

drawings to judge from, it seems likely that the original Saint

Marie was very different than the one shown above.

In addition, the builder of Saint Marie, Charles

Boivin, had lived and worked in Rouen, France, as a builder

and cabinet maker for some years before going to Saint Marie

in 1635.

|

|

|

Royal

Chapel of the Mohawks

The Royal Chapel of the Mohawks in Brantford has

been reoriented since it was built in 1785, but the basic shape

and size remain intact. The architects for the church were John

Smith and John Wilson, two Loyalists from the Mohawk Valley.

It is understated Georgian, made of wood frame.

The roof is steeply pitched and narrow eaved,

as are most Loyalist churches in both Upper and Lower Canada.

(see www.ontario architecture.com/loyalist.htm)

When the building was completed in 1785, this

portion of the province was still under the vast territory known

as Quebec.

The inside of the church is spectacular tongue

and grove work. Photographs are not permitted.

|

|

|

Royal

Chapel of the Mohawks

When the Mohawks relocated in Ontario after the

American Revolution, they left all of their lands behind. To

compensate for this loss they were granted 760 000 acres on

the Grand River. The crown agreed to construct two mills, a

school and a chapel for their use. This chapel was completed

in 1785. There have been continuous services in the church since

the doors were opened over 220 years ago.

When first built, the building was oriented to

have the front door opening onto the Grand River which runs

to the east of the building (on the left). The river was subsequently

diverted and the land between the church and the river became

more a swamp than a river. Road access became available shortly

thereafter, and the chapel's door was reallocated to the west

side where it remains.

|

|

|

First

Nations Resources

|

Books

Diamond, Jared , Guns,

Germs and Steel, New York, London: Norton,

1997

Griffiths, Nicholas and Fernando Cervantes,

Spiritual Encounters: Interaction

between Christianity and Native Religions in Colonial

America, Lincoln, Nebraska:

University of Nebraska Press, 1999

MacRae, Marion and Anthony Adamson , Hallowed

Walls;Church Architecture of Upper Canada,

Toronto,Vancouver: Clark Irwin, 1975

Parker, Arthur C., The Indian

How Book, New York,Dover, 1975

Wagner, Norman E. and Lawrence E. Toombs, The

Moyer Site: A Prehistoric Village in Waterloo County,

Waterloo, Ontario: Wilfrid Laurier University, 1973

Canadian Journal of native

Studies

Fiction

Margaret Atwood Surfacing

|

|

Films

Aboriginal Architecture: Living

Architecture , NFB

Fiction

Clearcut and Thunderheart

are the best, but anything with Graham Greene

will be good.

The Brave, Johnny Depp

The Last of the Mohicans,

Danial Day Lewis

Dances with Wolves,

Kevin Costner

Websites

http://www.ucs.mun.ca/~lrankin/lgl.html

www.civilization.ca/cmc/archeo/oracles/draper/drape.htm

http://www.mohawkchapel.ca/history.html

http://www.ontarioarchaeology.on.ca

|

|

|